P. Justin Popovich

La seguente lettera è stata indirizzata dall’archimandrita serbo P. Justin Popovic di beata memoria, padre spirituale del monastero di Celie Valjevo (Jugoslavia), al vescovo Jovan di Sabac e alla gerarchia serba il 7 maggio 1977, con la richiesta di trasmettere questa lettera al Santo Sinodo e al Consiglio dei Vescovi della Chiesa Ortodossa Serba. La sua rilevanza non è diminuita con il passare degli anni… e forse è aumentata alla luce dei recenti avvenimenti che stanno scuotendo la cattolicità Ortodossa. Si vede bene come alcuni temi, ancora oggi centrali e divisivi, abbiano avuto una lunga gestazione nella storia. La teologia del Padre Justin ci illumina sui veri principi ecclesiologici della Santa Ortodossia che non possono essere scambiati “per un piatto di lenticchie” a pena della stessa salvezza dell’uomo e del mondo.

Non molto tempo fa a Chambesy, vicino a Ginevra, ha avuto luogo la “Prima Conferenza preconciliare” (21-28 novembre 1976). Dopo aver letto e studiato gli atti e le risoluzioni di questo convegno, pubblicati dal “Segretariato per la preparazione del Santo e Grande Concilio della Chiesa Ortodossa” a Ginevra, sento nella mia coscienza l’urgente necessità evangelica, come membro del La Santa e Cattolica Chiesa Ortodossa, anche se come suo più umile servo, di rivolgermi a Vostra Grazia e, attraverso di Lei, al Santo Sinodo dei Vescovi della Chiesa Serba, con questa esposizione che deve esprimere le mie dolorose considerazioni per il futuro Concilio. Prego Vostra Grazia e i Reverendissimi Vescovi di ascoltarmi con zelo evangelico e di ascoltare questo grido di una coscienza ortodossa, che, grazie a Dio, non è né sola né isolata nel mondo ortodosso quando si parla di quel concilio.

1. Dai verbali e dalle risoluzioni della “Prima Conferenza preconciliare”, che, per qualche motivo sconosciuto, si è tenuta a Ginevra, dove è difficile trovare anche solo poche centinaia di fedeli ortodossi, risulta chiaro che questa conferenza ha preparato e ha ordinato un nuovo catalogo di temi per il futuro “Gran Concilio” della Chiesa Ortodossa. Questa non era una di quelle “Conferenze pan-ortodosse”, come quelle che si tenevano a Rodi e successivamente altrove; né è stato il “Pro-Sinodo”, che è stato all’opera finora; si trattava del “Primo Convegno preconciliare”, che avviava la preparazione diretta alla celebrazione di un concilio ecumenico. Inoltre, questo convegno non ha iniziato i suoi lavori sulla base del “Catalogo dei temi, il concilio deve essere “di breve durata” e occuparsi di “un numero limitato di argomenti”; inoltre, secondo le parole del metropolita Meliton, “il Concilio deve approfondire le questioni scottanti che ostacolano il normale funzionamento del sistema che collega le Chiese locali in una sola Chiesa ortodossa…” (“Atti”, p. 55) Tutto ciò obbliga a chiedersi: cosa significa? Perché tutta questa fretta nella preparazione? Dove ci porterà tutto questo?

2. La questione della preparazione e della celebrazione di un nuovo concilio ecumenico della Chiesa ortodossa non è né nuova né recente in questo ultimo secolo della storia della Chiesa. La questione era già stata proposta durante la vita dello sfortunato patriarca di Costantinopoli, Meletios Metaxakis – il celebre e presuntuoso modernista, riformatore e autore di scismi all’interno dell’Ortodossia – al suo Congresso pan-ortodosso tenutosi a Costantinopoli nel 1923. Fu raccomandato che il concilio si tenesse nella città di Nis nel 1925, ma poiché Nis non si trovava nel territorio del Patriarcato ecumenico, il concilio non fu convocato, probabilmente proprio per questo motivo. In generale, a quanto pare, Costantinopoli ha ipotizzato il monopolio della “Pan-Ortodossia”, di tutti i “Congressi”, delle “Conferenze”, “Pro-sinodi” e “concili”. Più tardi, nel 1930, presso il monastero di Vatopedi, ebbe luogo la Commissione preparatoria delle Chiese ortodosse. Essa definì il catalogo degli argomenti per il futuro pro-sinodo ortodosso, che avrebbe dovuto preludere al concilio ecumenico.

Dopo la Seconda Guerra Mondiale fu la volta del Patriarca Atenagora di Costantinopoli con le sue Conferenze Panortodosse a Rodi (sempre esclusivamente nel territorio del Patriarcato di Costantinopoli). Il primo di essi, nel 1961, prevedeva la preparazione di un Concilio pan-ortodosso a condizione che fosse convocato un pro-sinodo, e confermava un catalogo di temi già preparato dal Patriarcato di Costantinopoli: otto capitoli interi con quasi quaranta argomenti principali e il doppio dei paragrafi e sottoparagrafi.

Dopo le Conferenze di Rodi II e III (1963 e 1964), nel 1966 si tenne la Conferenza di Belgrado. Dapprima questa fu chiamata Quarta Conferenza Panortodossa (Glasnik della Chiesa Ortodossa Serba, n. 10, 1966 e documenti in greco pubblicati sotto questo titolo), ma in seguito fu ridotta dal Patriarcato di Costantinopoli al grado di Inter-Commissione Ortodossa, affinché la conferenza successiva, tenutasi nel “territorio” di Costantinopoli (il Centro Ortodosso del Patriarcato Ecumenico a Chambesy-Ginevra) nel 1968, potesse essere acclamata al suo posto come Quarta Conferenza Pan-Ortodossa. In questa conferenza, a quanto pare, i suoi impazienti organizzatori si sono affrettati ad abbreviare il percorso verso il concilio, poiché dall’enorme catalogo di Rodi (il loro lavoro, tuttavia, e di nessun altro) hanno preso solo i primi sei argomenti e hanno definito una nuova procedura di lavoro. Allo stesso tempo è stata varata una nuova istituzione: la Commissione preparatoria interortodossa, indispensabile per il coordinamento dei lavori sui temi. Inoltre è stata istituita la Segreteria per la Preparazione del Concilio; si trattava infatti di un vescovo di Costantinopoli a cui venne assegnato l’incarico, con sede nella suddetta Ginevra – nello stesso tempo furono respinte le proposte di includere nel Segretariato altri membri ortodossi. Questa commissione preparatoria e il Segretariato, per desiderio di Costantinopoli, si riunirono a Chambésy nel giugno 1971. In tale riunione esaminarono e approvarono all’unanimità gli abstract dei sei argomenti selezionati, che successivamente furono pubblicati in diverse lingue e presentati, come tutto il precedente lavoro di preparazione al concilio, alle critiche spietate dei teologi ortodossi. Le critiche dei teologi ortodossi (tra cui il mio Memorandum inviato a suo tempo per Vostra Grazia e, con l’approvazione di Vostra Grazia, al Santo Sinodo dei Vescovi, e successivamente approvato da molti teologi ortodossi e pubblicato in varie lingue del mondo ortodosso) sembrano spiegare perché la decisione della Commissione preparatoria di Ginevra di convocare nel 1972 la Prima Conferenza preconciliare per la revisione del catalogo di Rodi, di fatto non fu rispettata quell’anno, e la conferenza ebbe luogo solo con grande ritardo.

Questa Prima Conferenza Preconciliare si tenne solo nel novembre del 1976, sempre, ovviamente, sul “territorio” costantinopolitano, nel suddetto centro di Chambesy, vicino a Ginevra. Come risulta dagli atti e dalle risoluzioni, appena pubblicati e da me attentamente studiati, questo convegno ha riesaminato il catalogo di Rodi a tal punto che le delegazioni partecipanti ai lavori delle varie commissioni hanno scelto all’unanimità solo dieci temi per il concilio (dei sei originari solo tre figuravano nell’elenco!), mentre una trentina di temi, scelti non all’unanimità, furono riservati allo “studio particolare nelle singole Chiese” sotto forma di “problematiche della Chiesa ortodossa” (un concetto del tutto estraneo all’Ortodossia). In futuro questi temi potrebbero diventare oggetto di “esami ortodossi” e magari essere inseriti nel catalogo. Come già affermato, questo convegno ha modificato il processo e la metodologia di elaborazione dei temi e dei lavori preparatori del concilio che, ripeto, secondo gli organizzatori sia di Costantinopoli che di altri luoghi, dovrebbero svolgersi “al più presto possibile”. Da tutto ciò risulta chiaro ad ogni cristiano ortodosso che il Primo Convegno preconciliare non ha proposto nulla di sostanzialmente nuovo, ma continua piuttosto a condurre gli animi ortodossi e le coscienze di molti in labirinti sempre nuovi costituiti da ambizioni personali. Questo è il motivo per cui, a quanto pare, il Concilio ecumenico è in preparazione dal 1923, e il motivo per cui al momento si desidera realizzarlo in fretta.

3. Tutte le “problematiche” contemporanee riguardanti i temi del futuro concilio, l’incertezza e la mutevolezza della loro invenzione, la loro determinazione, la loro “catalogazione” artificiale, così come tutti i nuovi cambiamenti e “revisioni”, dimostrano ad ogni vera coscienza ortodossa una sola cosa: che al momento non ci sono problemi seri o urgenti che giustifichino la convocazione e la celebrazione di un nuovo concilio ecumenico della Chiesa ortodossa. E se tuttavia esistesse un tema degno di essere oggetto della convocazione e della celebrazione di un concilio ecumenico, non è noto ai presenti promotori, organizzatori e redattori di tutti i suddetti “Convegni” con i loro precedenti e attuali “cataloghi”. Se così non fosse, come spiegare allora che, a partire dall’incontro di Costantinopoli del 1923, passando per Rodi nel 1961 e fino a Ginevra nel 1976, le “tematiche” e le “problematiche” del futuro concilio siano state costantemente cambiate? Le modifiche riguardano il numero, l’ordine, i contenuti e gli stessi criteri impiegati per il Catalogo dei Temi che dovrà costituire l’opera di questo grande e unico corpo ecclesiastico che è il Santo Concilio Ecumenico della Chiesa Ortodossa, come è stato e come deve essere. In realtà, tutto ciò manifesta e sottolinea non solo la consueta incoerenza, ma anche un’evidente incapacità di comprendere la natura dell’Ortodossia da parte di coloro che attualmente, nell’attuale situazione, e in tal modo imporrebbe il loro “Concilio” alle Chiese ortodosse – un’ignoranza e un’incapacità di sentire o comprendere ciò che un vero concilio ecumenico ha significato e significa sempre per la Chiesa ortodossa e per il pleroma dei suoi fedeli che portano il nome di Cristo. Perché se percepissero e si rendessero conto di questo, saprebbero innanzitutto che mai nella storia e nella vita della Chiesa ortodossa un singolo concilio, per non parlare di un evento così eccezionale e pieno di grazia (come la stessa Pentecoste) come un concilio ecumenico, ha cercato e inventato argomenti in questo modo artificiale per i suoi lavori e le sue sessioni; – mai sono state convocate conferenze, congressi, pro-sinodi e altre riunioni artificiali, sconosciute alla tradizione conciliare ortodossa, e in realtà prese in prestito da organizzazioni occidentali estranee alla Chiesa di Cristo.

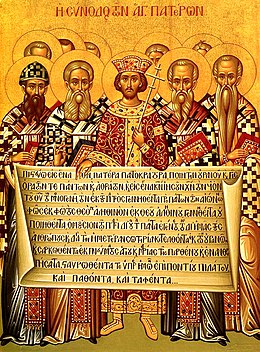

La realtà storica è perfettamente chiara: i santi Concili dei Santi Padri, convocati da Dio, sempre, sempre avevano davanti a sé una, o al massimo due o tre questioni poste dall’estrema gravità delle grandi eresie e scismi che snaturavano la fede ortodossa. La fede ha lacerato la Chiesa e ha messo seriamente in pericolo la salvezza delle anime umane, la salvezza del popolo di Dio ortodosso e dell’intera creazione di Dio. Pertanto, i concili ecumenici hanno sempre avuto un carattere cristologico, soteriologico, ecclesiologico, il che significa che il loro unico e centrale tema – la loro Buona Novella – è sempre stato il Dio-Uomo Gesù Cristo e la nostra salvezza in Lui, la nostra divinizzazione in Lui. Sì, Lui, il Figlio di Dio, unigenito e consustanziale, incarnato; Lui – l’eterno Capo del Corpo della Chiesa per la salvezza e la divinizzazione dell’uomo; Lui – interamente nella Chiesa per la grazia dello Spirito Santo, per la vera fede in Lui, per la fede ortodossa.

Questo è il tema veramente ortodosso, apostolico e patristico, il tema immortale della Chiesa del Dio-Uomo, per tutti i tempi, passati, presenti e futuri. Soltanto questo potrà essere l’oggetto di un eventuale futuro concilio ecumenico della Chiesa ortodossa, e non un qualche catalogo scolastico-protestante di argomenti che non hanno alcuna relazione essenziale con la vita spirituale e l’esperienza dell’Ortodossia apostolica nel corso dei secoli, poiché non è altro che un serie di teoremi anemici e umanistici. L’eterna cattolicità della Chiesa ortodossa e di tutti i suoi concili ecumenici consiste nella Persona onnicomprensiva dell’Uomo-Dio, il Signore Cristo. Questa è la realtà centrale e universale, il tema dei Concili ortodossi, questo è il mistero e la realtà unici del Dio-Uomo, sul quale si edifica e si sostiene la Chiesa Ortodossa di Cristo con tutti i concili ecumenici e tutta la sua realtà storica. Su questo fondamento dobbiamo costruire, anche oggi, davanti al cielo e alla terra, e non sui temi scolastico-protestanti e umanistici utilizzati dai delegati o delegazioni ecclesiastiche di Costantinopoli o di Mosca, che in questo momento storico amaro e critico si presentano come “leader e rappresentanti” della Chiesa ortodossa nel mondo.

4. Dagli atti dell’ultima Conferenza preconciliare di Ginevra, come in situazioni simili precedenti, risulta chiaro che le delegazioni ecclesiastiche di Costantinopoli e di Mosca differiscono poco tra loro rispetto ai problemi e ai temi posti come oggetto del lavorare per il futuro consiglio. Hanno gli stessi argomenti, quasi lo stesso linguaggio, la stessa mentalità, simili ambizioni. Ciò, tuttavia, non è una sorpresa. Chi rappresentano infatti in questo momento, quale Chiesa e quale popolo di Dio? La gerarchia costantinopolitana in quasi tutti i raduni pan-ortodossi è composta principalmente da metropoliti e vescovi titolari, da pastori senza greggi e senza responsabilità pastorale concreta davanti a Dio e al proprio gregge vivente. Chi rappresentano e chi rappresenteranno al futuro consiglio? Tra i rappresentanti ufficiali del Patriarcato ecumenico non ci sono vescovi delle isole greche dove si trovano veri greggi ortodossi; non ci sono vescovi diocesani greci provenienti dall’Europa o dall’America, per non parlare di altri vescovi – russi, americani, giapponesi, africani, che hanno grandi greggi ortodossi ed eccellenti teologi ortodossi. D’altra parte, l’attuale delegazione del Patriarcato di Mosca rappresenta davvero la santa e martire grande Chiesa russa e i milioni dei suoi martiri e confessori conosciuti solo da Dio? A giudicare da ciò che queste delegazioni dichiarano e difendono, ovunque si rechino fuori dall’Unione Sovietica, non rappresentano né esprimono il vero spirito e l’atteggiamento della Chiesa ortodossa russa e del suo fedele gregge ortodosso, poiché il più delle volte queste delegazioni mettono le cose di Cesare prima delle cose di Dio. Il comandamento scritturale, tuttavia, è diverso: “Sottomettetevi piuttosto a Dio che agli uomini” (Atti 5:29).

Inoltre, è corretto, è ortodosso avere tali rappresentanze delle Chiese ortodosse nei vari incontri panortodossi a Rodi o a Ginevra? I rappresentanti di Costantinopoli che hanno avviato questo sistema di rappresentanza delle Chiese ortodosse nei concili e coloro che accettano questo principio che, secondo la loro teoria, è in accordo con il “sistema delle Chiese locali autocefale e autonome” – hanno dimenticato che tale principio contraddice la tradizione conciliare dell’Ortodossia. Purtroppo questo principio di rappresentanza è stato accettato rapidamente e da tutti gli altri ortodossi: a volte silenziosamente, a volte con proteste votate, ma dimenticando che la Chiesa ortodossa, per sua natura e per la sua costituzione dogmaticamente immutabile, è episcopale e centrata nei vescovi. Perché il vescovo e i fedeli raccolti attorno a lui sono espressione e manifestazione della Chiesa come Corpo di Cristo, soprattutto nella santa Liturgia: la Chiesa è apostolica e cattolica solo in virtù dei suoi vescovi, in quanto sono capi di veri unità ecclesiastiche, le diocesi. Allo stesso tempo, le altre forme storicamente successive e variabili di organizzazione ecclesiastica della Chiesa ortodossa: metropoli, arcidiocesi, patriarcati, pentarchie, autocefalie, autonomie, ecc., per quante possano essere o saranno, possono avere o fare, non hanno un significato determinante e decisivo nel sistema conciliare della Chiesa ortodossa. Inoltre, essi possono costituire un ostacolo al corretto funzionamento del principio conciliare se ostacolano e rifiutano il carattere e la struttura episcopale della Chiesa e delle Chiese. Qui, senza dubbio, si trova la differenza principale tra l’ecclesiologia ortodossa e quella papale.

Se è così, come possono essere rappresentate secondo il principio della delega, cioè con lo stesso numero di delegati, ad esempio, la Chiesa ceca e quella rumena? O, ancor più, i Patriarcati di Russia e di Costantinopoli? Quali gruppi di fedeli rappresentano i primi vescovi e quali i secondi? Negli ultimi tempi il Patriarcato di Costantinopoli ha prodotto una moltitudine di vescovi e metropoliti, quasi tutti titolari e fittizi. È possibile che si tratti di una misura preparatoria per garantire al futuro “Concilio ecumenico”, con la sua moltitudine di titoli, la maggioranza dei voti per le ambizioni neo-papali del Patriarcato di Costantinopoli? D’altro canto, le Chiese apostolicamente zelanti nel lavoro missionario, come la Metropolia americana, la Chiesa russa all’estero, la Chiesa giapponese e altri non possono avere un solo rappresentante!

Dov’è in tutto ciò il principio cattolico dell’Ortodossia? Che tipo di concilio ecumenico sarà questo della Chiesa Ortodossa di Cristo? Già alla Conferenza di Ginevra, Ignatios, metropolita di Laodicea e rappresentante del Patriarcato di Antiochia, aveva affermato con tristezza: “Percepisco un disagio, perché si danneggia l’esperienza conciliare che è il fondamento della Chiesa ortodossa”.

5. Tuttavia, Costantinopoli e alcuni altri non vedono l’ora di convocare il “concilio”. È innanzitutto in accordo con i loro desideri e con le loro insistenza che la Prima Conferenza preconciliare di Ginevra ha deciso che “il Concilio debba essere convocato al più presto possibile”, che questo Concilio debba essere “di breve durata” e che debba “prendere in considerazione un piccolo numero di argomenti.” E vengono citati i dieci temi scelti. I primi quattro temi sono: la diaspora; la questione dell’autocefalia ecclesiastica e le condizioni per la sua proclamazione; l’autonomia e la sua proclamazione; i dittici, cioè l’ordine di precedenza tra le Chiese ortodosse.

L’obiettività evangelica obbliga a notare che la condotta del presidente della Conferenza preconciliare, il metropolita Meliton, è stata dispotica e inadatta a un concilio. Ciò emerge chiaramente da ogni pagina degli atti pubblicati del convegno. Lì si afferma chiaramente e in maniera trasparente che “questo Santo e Grande Concilio della Chiesa Ortodossa che si sta preparando non deve essere considerato come unico, escludendo l’ulteriore convocazione di altri Santi e Grandi Concili” (“Atti”, pp. 18, 20, 50, 55, 60).

Di fronte a tutto ciò, una coscienza evangelicamente sensibile non può fare a meno di porsi la domanda scottante: qual è il vero fine di un concilio convocato così frettolosamente e in modo così prepotente?

Reverendissimi Vescovi, non riesco a liberarmi dall’impressione e dalla convinzione che tutto ciò indichi il segreto desiderio di alcune note personalità del Patriarcato di Costantinopoli: che il primo in onore dei Patriarcati ortodossi imponga le sue idee e procedure a tutte le Chiese ortodosse autocefale , e in generale sul mondo ortodosso e sulla diaspora ortodossa, e sancire tale intenzione neopapista mediante un “concilio ecumenico”. Per questo motivo, tra i dieci temi selezionati per il concilio sono stati inseriti, anzi sono i primi, proprio quei temi che rivelano l’intenzione di Costantinopoli di sottomettere a sé l’intera diaspora ortodossa – e cioè il mondo intero! e di garantirsi il diritto esclusivo di concedere l’autocefalia e l’autonomia in generale a tutte le Chiese ortodosse del mondo, presenti e future, e allo stesso tempo di determinarne l’ordine e il rango a propria discrezione (questo è esattamente ciò che implica la questione dei dittici, perché non riguardano solo l’”ordine di commemorazione liturgica”, ma anche l’ordine di precedenza nei concili, ecc.)

Mi inchino con riverenza davanti alle conquiste secolari della Grande Chiesa di Costantinopoli, e davanti alla sua croce attuale, che non è né piccola né facile, che, secondo la natura delle cose, è la croce di tutta la Chiesa – poiché, come dice L’Apostolo: “Quando un membro soffre, tutto il corpo soffre”. Riconosco inoltre il rango canonico e il primo posto in onore di Costantinopoli tra le Chiese ortodosse locali, che sono uguali in onore e diritti. Ma non sarebbe conforme al Vangelo se a Costantinopoli, a causa delle difficoltà in cui si trova ora, si permettesse di portare l’intera ortodossia sull’orlo del baratro, come avvenne nello pseudoconcilio di Firenze, oppure canonizzare e dogmatizzare particolari forme storiche che, in un dato momento, possano trasformarsi da ali in pesanti catene, legando la Chiesa e la sua presenza trasfigurante nel mondo. Siamo franchi: la condotta dei rappresentanti di Costantinopoli negli ultimi decenni è stata caratterizzata dalla stessa malsana inquietudine, dalla stessa condizione spiritualmente malata che portò la Chiesa al tradimento e alla disgrazia di Firenze nel XV secolo. (Né la condotta della stessa Chiesa sotto il giogo turco è stata un esempio di tutti i tempi. Sia il giogo fiorentino che quello turco erano pericolosi per l’Ortodossia.) Con la differenza che oggi la situazione è ancora più inquietante: un tempo Costantinopoli era un organismo vivo con milioni di fedeli: seppe superare senza indugio la crisi provocata dai corsi esterni come anche la tentazione di sacrificare la fede e il Regno di Dio per i beni di questo mondo. Oggi, però, ha solo metropoliti senza fedeli, vescovi che non hanno nessuno da guidare (cioè senza diocesi), che tuttavia desiderano controllare i destini dell’intera Chiesa. Oggi non deve, non può esserci una nuova Firenze! Né la situazione attuale può essere paragonata alle difficoltà del giogo turco. Lo stesso ragionamento vale per il Patriarcato di Mosca. Si permetterà che le sue difficoltà o quelle di altre Chiese locali sotto il comunismo ateo determinino il futuro dell’Ortodossia?

Le sorti della Chiesa non sono né possono più essere nelle mani dell’imperatore bizantino o di qualunque altro sovrano. Non è il controllo di un patriarca o di alcuno dei potenti di questo mondo, nemmeno in quello della “Pentarchia” o delle “autocefalie” (intese in senso stretto). Per la potenza di Dio la Chiesa è cresciuta fino a diventare una moltitudine di Chiese locali con milioni di fedeli, molti dei quali ai nostri giorni hanno suggellato con il loro sangue la loro successione apostolica e la fedeltà all’Agnello. E nuove Chiese locali sembrano sorgere all’orizzonte, come quella giapponese, quella africana e quella americana, e la loro libertà nel Signore non deve essere tolta da nessuna “super-Chiesa” di tipo papale (cfr Canone 8, III Concilio Ecumenico), poiché ciò significherebbe un attacco all’essenza stessa della Chiesa. Senza il loro concorso è inconcepibile la soluzione di qualsiasi questione ecclesiastica di rilevanza ecumenica, per non parlare della soluzione delle questioni che li riguardano immediatamente, cioè il problema della diaspora. La secolare lotta dell’Ortodossia contro l’assolutismo romano è stata una lotta proprio per la libertà della Chiesa locale in quanto cattolica e conciliare, completa e integra in se stessa. Dobbiamo oggi percorrere la strada della prima e caduta Roma, o di qualche “seconda” o “terza” simile ad essa? Dobbiamo credere che Costantinopoli, che nelle persone dei suoi santi e grandi gerarchi, del suo clero e del suo popolo, si è opposta così coraggiosamente nei secoli passati al protezionismo e all’assolutismo romano, si stia oggi preparando a ignorare le tradizioni conciliari dell’Ortodossia e a scambiarle con il surrogato neopapale di una “seconda”, “terza” o altra sorta di Roma?

6. Venerabilissimi Padri! Tutti gli ortodossi vedono e si rendono conto di quanto sia importante, quanto sia significativa oggi la questione della diaspora ortodossa sia per la Chiesa ortodossa in generale che per tutte le Chiese ortodosse individualmente. Si può risolvere questa questione, come vogliono Costantinopoli o Mosca, senza fare riferimento, senza la partecipazione dei fedeli ortodossi, pastori e teologi della stessa diaspora, che ogni giorno aumenta? Il problema della diaspora, senza dubbio, è una questione ecclesiale di eccezionale importanza; è una questione che è emersa per la prima volta nella storia con tanta forza e significato. Per la sua soluzione ci sarebbe davvero motivo di convocare un concilio veramente ecumenico a cui partecipino veramente tutti i vescovi ortodossi di tutte le Chiese ortodosse. Un’altra questione che, a nostro avviso, potrebbe e dovrebbe essere esaminata in un autentico concilio ecumenico della Chiesa ortodossa è quella dell’ecumenismo. Si tratta, propriamente, di una questione ecclesiologica che riguarda la Chiesa come unità e organismo teandrico, unità e organismo che sono messi in dubbio dal sincretismo ecumenico contemporaneo. È anche legata alla questione dell’uomo, per il quale il nichilismo delle ideologie contemporanee, soprattutto atee, ha scavato una fossa senza speranza di resurrezione. Entrambe le questioni possono essere risolte correttamente e in modo ortodosso solo procedendo dai fondamenti teandrici degli antichi e veri concili ecumenici. Per il momento, tuttavia, lascio da parte questi problemi per non appesantire questo appello con nuove discussioni e per non ampliarlo eccessivamente.

La questione della diaspora è, quindi, allo stesso tempo grave ed estremamente importante nell’Ortodossia contemporanea. Tuttavia, esistono attualmente le condizioni che garantirebbero che la sua soluzione in concilio sia corretta, ortodossa e secondo l’insegnamento dei Santi Padri? È possibile, infatti, che ci sia una rappresentanza libera e reale di tutte le Chiese ortodosse in un concilio ecumenico senza che influenze esterne le disturbino? I rappresentanti di molti, soprattutto delle Chiese sotto regimi militanti atei, sono davvero in grado di esprimere e difendere i principi ortodossi? Può una Chiesa che rinnega i propri martiri essere un autentico confessore della Croce del Golgota, ovvero portatrice dello spirito e della coscienza conciliare della Chiesa di Cristo? Prima che si tenga un concilio, chiediamoci se sarà possibile che in essa parli la coscienza di milioni di nuovi martiri, resi bianchi dal sangue dell’Agnello. L’esperienza della storia insegna che ogni volta che la Chiesa viene crocifissa, ciascuno dei suoi membri è chiamato a soffrire per la sua Verità, e a non dibattere problemi artificiali o cercare false risposte a domande vere – “pescando in acque torbide” per soddisfare le ambizioni personali. Non ricordiamo che finché le persecuzioni della Chiesa durarono, non furono convocati concili ecumenici – il che non significa che la Chiesa di Dio in quei tempi non vivesse o non funzionasse in modo conciliare. Al contrario, l’epoca delle persecuzioni fu il suo periodo più ricco di frutti. E quando in seguito si riunì il Primo Concilio Ecumenico, si riunirono anche i confessori con le loro ferite e cicatrici, i vescovi provati dal fuoco della sofferenza, che allora potevano testimoniare liberamente di Cristo come Dio e Signore. Il loro spirito sarà presente anche in questo momento? In altre parole, i vescovi del nostro tempo che sono simili ai martiri saranno presenti al concilio che si sta preparando, in modo che questo concilio possa pensare secondo lo Spirito Santo e parlare e decidere secondo Dio, e che in esso non siano ascoltati soprattutto coloro che non sono liberi dall’influenza delle potenze di questo mondo? Consideriamo, ad esempio, il gruppo di vescovi della Chiesa russa fuori dalla Russia che, con tutta la loro debolezza umana, portano su di sé i vincoli del Signore e della Chiesa russa che è fuggita nel deserto dalle persecuzioni non inferiori a quelle di Diocleziano: questi vescovi sono stati esclusi in anticipo da Mosca e Costantinopoli dalla partecipazione al concilio, e in questo modo condannati al silenzio. Pensiamo a quei vescovi della Russia e di altri Paesi apertamente atei che non potranno partecipare liberamente al concilio, né parlare e prendere decisioni liberamente; ad alcuni di loro non sarà nemmeno permesso di partecipare al concilio. Per non parlare dell’impossibilità per loro o per le loro Chiese di prepararsi in modo degno per un’occasione così grande e significativa. Non è questa una prova più che sufficiente del fatto che al concilio la coscienza della Chiesa martire e la coscienza del pleroma ecclesiastico saranno entrambe silenziose, che ai loro rappresentanti non sarà permesso nemmeno di entrare – come è successo con uno dei più illustri testimoni della Chiesa perseguitata all’assemblea di Nairobi (mi riferisco in particolare a Solzhenitsyn)?

Possiamo lasciare da parte la questione di quanto possa essere morale o addirittura normale che in un momento in cui il Signore Gesù Cristo e la fede in Lui sono crocifissi in modo più terribile che mai, i Suoi seguaci debbano decidere chi sarà il primo tra loro. In un tempo in cui Satana cerca non solo il corpo ma l’anima stessa dell’uomo e del mondo, quando l’umanità è minacciata di autodistruzione, è morale e normale che i discepoli di Cristo si occupino delle stesse domande (e allo stesso modo) delle ideologie anticristiane contemporanee – ideologie che vendono il Pane della Vita per un piatto di lenticchie?

Tenendo presente tutto ciò e dolorosamente consapevole della situazione della Chiesa ortodossa contemporanea e del mondo in generale – che non è sostanzialmente cambiata dal mio ultimo appello al Santo Consiglio dei Vescovi (maggio 1971) la mia coscienza mi obbliga ancora una volta a rivolgermi con insistenza e supplica al Santo Sinodo episcopale della Chiesa serba martirizzata: la nostra Chiesa serba si astenga dal partecipare ai preparativi del “concilio ecumenico”, anzi dal partecipare al concilio stesso. Perché se questo concilio, Dio non voglia, dovesse effettivamente realizzarsi, ci si può aspettare solo un tipo di risultato: scismi, eresie e la perdita di molte anime. Considerando la questione dal punto di vista dell’esperienza apostolica, patristica e storica della Chiesa, un tale concilio, invece di guarire, non farà altro che aprire nuove ferite nel corpo della Chiesa e infliggerle nuovi problemi e nuove disgrazie.

Mi raccomando alla preghiera santa e apostolica dei Padri del Santo Sinodo dei Vescovi della Chiesa Ortodossa Serba.

L’indegno archimandrita Justin

(padre spirituale del monastero di Chelie)

Vigilia della festa di San Giorgio, 1977 Monastero di Chelie, Valjevo (Jugoslavia)

ENGLISH VERSION

On a Summoning of the Great Council of the Orthodox Church

Archimandrite Justin Popovich

The following letter was addressed by Archimandrite Dr. Justin Popovic of blessed memory, spiritual father of the monastery of Celie Valjevo (Yugoslavia), to Bishop Jovan of Sabac and the Serbian hierarchy on May 7, 1977, with the request to transmit this letter to the Holy Synod and the Council of Bishops of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Its relevance has not diminished with the passing years… and perhaps has increased in the light of the recent scandalous and unOrthodox events on Mount Athos.

Not long ago in Chambesy, near Geneva, the “First Pre-Conciliar Conference” took place (November 21-28, 1976). After reading and studying the acts and resolutions of this conference, published by the “Secretariat for the Preparation of the Holy and Great Council of the Orthodox Church” in Geneva, I feel in my conscience the urgent, evangelical necessity, as a member of the Holy and Catholic Orthodox Church, even though its humblest servant, to turn to Your Grace and, through you, to the Holy Council of Bishops of the Serbian Church, with this exposition that must express my grievous considerations for the future council. I beg Your Grace and the Most Reverend Bishops to hear me with evangelical zeal and to listen to this cry of an Orthodox conscience, which, thanks be to God, is neither alone nor isolated in the Orthodox world whenever there is mention of that council.

1. From the minutes and resolutions of the “First Pre-Conciliar Conference,” which, for some unknown reason, was held in Geneva, where it is difficult to find even a few hundred Orthodox faithful, it is clear that this conference prepared and ordained a new catalogue of topics for the future “Great Council” of the Orthodox Church. This was not one of those “Pan-Orthodox Conferences,” such as were held on Rhodes and subsequently elsewhere; nor was it the “Pro-Synod,” which has been at work until now; this was the “First Pre-Conciliar Conference,” initiating the direct preparation for the celebration of an ecumenical council. Moreover, this conference did not begin its work on the foundation of the “Catalogue of Topics,” established at the first Pan-Orthodox Conference in 1961 on Rhodes and unelaborated up until 1971, instead it compiled a revision of this catalogue and set forth its own new “Catalogue of Topics” for the council. Apparently, however, not even this catalogue is definitive, for it will very likely again be altered and supplemented. Lately, the Conference has also reconsidered the methodology formerly adopted in the planning and final preparation of topics for the council. It abbreviated this entire process in view of its haste and urgency to summon the council as soon as possible. For, according to the explicit declaration of Metropolitan Meliton, presiding chairman of the Conference, the Patriarchate of Constantinople and certain others “are hastening to summon” and celebrate the future council: the council must be “of short duration” and occupy itself with “a limited number of topics”; moreover, in the words of Metropolitan Meliton, “The Council must delve into the burning questions that obstruct the normal functioning of the system linking up the local Churches, into the one, single Orthodox Church…” (“Acts,” p.55) All of this obliges us to ask: what does it mean? Why all this haste in the preparation? Where is all of this going to lead us?

2. The questions of the preparation and celebration of a new ecumenical council of the Orthodox Church is neither new nor recent in this century of the history of the Church. The matter was already proposed during the lifetime of that hapless Patriarch of Constantinople, Meletios Metaxakis – the celebrated and presumptuous modernist, reformer, and author of schisms within Orthodoxy – at his Pan-Orthodox Congress held in Constantinople in 1923. (At this time it was recommended that the council be held in the city of Nis in 1925, but since Nis was not in the territory of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, the council was not convened, probably for that very reason. In general, as it appears, Constantinople has assumed the monopoly of “Pan-Orthodoxy,” of all the “Congresses,” “Conferences,” “Pro-Synods” and “Councils.”) Later on, in 1930, at the monastery of Vatopedi, the Preparatory Commission of the Orthodox Churches took place. It defined the Catalogue of Topics for the Future Orthodox Pro-Synod, which should have been the prelude to the ecumenical council.

After the Second World War came the turn of Patriarch Athenagoras of Constantinople with his Pan-Orthodox Conferences on Rhodes (again, exclusively in the territory of the Patriarchate of Constantinople). The first of them, in 1961, called for the preparation of a Pan-Orthodox Council on condition that a pro-synod be summoned, and it confirmed a catalogue of topics which had already been prepared by the Patriarchate of Constantinople: eight full chapters with nearly forty primary topics and twice again as many paragraphs and subparagraphs.

After the Rhodes Conferences II and III (1963 and 1964), in 1966 the Belgrade Conference was held. At first this was called the Fourth Pan-Orthodox Conference (Glasnik of the Serbian Orthodox Church, No. 10, 1966 and documents in Greek published under this title), but later it was reduced by the Patriarchate of Constantinople to the grade of an Inter-Orthodox Commission, so that the succeeding conference, held in Constantinopolitan “territory” (the Orthodox Centre of the Ecumenical Patriarchate at Chambesy-Geneva) in 1968, might be acclaimed the Fourth Pan-Orthodox Conference in its place. At this conference, apparently, its impatient organizers hastened to shorten the path to the council, for from the enormous catalogue of Rhodes (their own work, however, and nobody else’s) they took only the first six topics and defined a new procedure of work. At the same time there was established a new institution: the Inter-Orthodox Preparatory Commission, indispensable for the coordination of work on the topics. Moreover, the Secretariat for the Preparation of the Council was also established; in fact, this meant a bishop of Constantinople who was assigned the task, with his seat at the above-named Geneva – at the same time proposals for including other Orthodox members in the Secretariat were rejected. This preparatory commission and the Secretariat, by wish of Constantinople held a meeting at Chambesy in June, 1971. At this meeting they examined and unanimously approved abstracts of the selected six topics, which subsequently were published in several languages and submitted, like all the previous work in preparation for the council, to the merciless criticism of Orthodox theologians. The criticisms of the Orthodox theologians (among them my Memorandum sent at that time through Your Grace and, with Your Grace’s approval, to the Holy Council of Bishops, and subsequently approved by many Orthodox theologians and published in various languages in the Orthodox world) apparently explain why the decision of the Preparatory Commission of Geneva to convene in 1972 the First Pre-Conciliar Conference for the revision of the catalogue of Rhodes, was in fact not observed that year, and the conference took place only with great delay.

This First Pre-Conciliar Conference was held only in November of 1976, again, of course, on Constantinopolitan “territory” at the above-named centre in Chambesy, near Geneva. As is clear from the acts and resolutions, only now just published, and which I have carefully studied, this conference re-examined the catalogue of Rhodes to such an extent that the delegations participating in the work of the various committees unanimously chose only ten topics for the council (only three of the original six were included in the list!), while about thirty topics, not unanimously chosen, were set aside for “particular study in the individual Churches” in the form of “problematics of the Orthodox Church” (a concept entirely alien to Orthodoxy). In the future these topics could become the subject of “Orthodox examinations” and perhaps be included in the catalogue. As already stated, this conference altered the process and methodology of elaborating the topics and the preparatory work of the council which, I repeat, according to the organizers from both Constantinople and other places, should take place “as soon as possible.” From all this, it is clear to every Orthodox Christian that the First Pre-Conciliar Conference has not come up with anything substantially new, but continues rather to lead Orthodox souls as well as the consciences of many into ever new labyrinths constituted by personal ambitions. This is the reason why, it would seem, the ecumenical council has been in preparation since 1923, and why at the present time it is desired to bring it to a hasty realization.

3. All the contemporary “problematics” concerning the topics of the future council, the uncertainty and mutability of their invention, their determination, their artificial “cataloguing,” as well as all the new changes and “revisions”, demonstrate to every true Orthodox conscience one thing only: that at the present time there are no serious or pressing problems that would justify the convening and celebration of a new ecumenical council of the Orthodox Church. And if, nevertheless, a topic should exist, worthy of being the object of the convocation and celebration of an ecumenical council, it is unknown to the present initiators, organizers and editors of all the above-mentioned “Conferences” with their previous and present “catalogues.” If this were not the case, then how is it to be explained that, beginning with the meeting in Constantinople in 1923, continuing through Rhodes in 1961 and up to Geneva in 1976, the “thematics” and “problematics” of the future council have been constantly changed? The alterations extend to the number, order, contents and the very criteria employed for the Catalogue of Topics that is to constitute the work of this great and unique ecclesiastical body – the Holy Ecumenical Council of the Orthodox Church, as it has been and as it must be. In reality, all of this manifests and underscores not only the usual lack of consistency, but also an obvious incapacity and failure to understand the nature of Orthodoxy on the part of those who at the present time, in the current situation, and in such a manner would impose their “Council” on the Orthodox Churches – an ignorance and inability to feel or to comprehend what a true ecumenical council has meant and always means for the Orthodox Church and for the pleroma of its faithful who bear the name of Christ. For if they sensed and realized this, they would first of all know that never in the history and life of the Orthodox Church has a single council, not to mention such an exceptional, grace-filled event (like Pentecost itself) as an ecumenical council, sought and invented topics in this artificial way for its work and sessions; – never have there been summoned such conferences, congresses, pro-synods, and other artificial gatherings, unknown to the Orthodox conciliar tradition, and in reality borrowed from Western organisations alien to the Church of Christ.

Historical reality is perfectly clear: the holy Councils of the Holy Fathers, summoned by God, always, always had before them one, or at the most two or three questions set before them by the extreme gravity of great heresies and schisms that distorted the Orthodox Faith, tore asunder the Church and seriously placed in danger the salvation of human souls, the salvation of the Orthodox people of God, and of the entire creation of God. Therefore, the ecumenical councils always had a Christological, soteriological, ecclesiological character, which means that their sole and central topic – their Good News – was always the God-Man Jesus Christ and our salvation in Him, our deification in Him. Yes, He – the Son of God, only-begotten and consubstantial, incarnate; He – the eternal Head of the Body of the Church for the salvation and deification of man; He – wholly in the Church by the grace of the Holy Spirit, by true faith in Him, by the Orthodox Faith.

This is the truly Orthodox, apostolic and patristic theme, the immortal theme of the Church of the God-Man, for all times, past, present and future. This alone can be the subject of any future possible ecumenical council of the Orthodox Church, and not some scholastic-protestant catalogue of topics having no essential relation to the spiritual life and experience of apostolic Orthodoxy down the ages, since it is nothing more than a series of anemic, humanistic theorems. The eternal catholicity of the Orthodox Church and of all her ecumenical councils consists in the all-embracing Person of the God-Man, the Lord Christ. This is the central and universal reality, the theme of Orthodox Councils, this is the unique mystery and reality of the God-Man, upon which the Orthodox Church of Christ is built and sustained with all ecumenical councils and all her historical reality. Upon this foundation we are to build, even today, in the sight of heaven and earth, and not upon the scholastic-protestant and humanistic topics employed by the ecclesiastical delegates or delegations of Constantinople or Moscow, who at this bitter and critical moment of history present themselves as the “leaders and representatives” of the Orthodox Church in the world.

4. From the acts of the last Pre-Conciliar Conference in Geneva, as in similar situations previously, it is clear that the ecclesiastical delegations of Constantinople and Moscow differ little from one another with respect to the problems and themes set forth as the subject of work for the future council. They have the same topics, almost the same language, the same mentality, similar ambitions. This, however, is no surprise. Whom do they in fact represent at the present moment, what Church and what people of God? The Constantinopolitan hierarchy at almost all the pan-Orthodox gatherings consists primarily of titular metropolitans and bishops, of pastors without flocks and without concrete pastoral responsibility before God and their own living flock. Whom do they represent and whom will they represent at the future council? Among the official representatives of the Ecumenical Patriarchate there are no hierarchs from the Greek islands where real Orthodox flocks are to be found; there are no Greek diocesan bishops from Europe or America, not to mention other bishops – Russian, American, Japanese, African, who have large Orthodox flocks and excellent Orthodox theologians. On the other hand, does the present delegation of the Moscow Patriarchate in fact represent the holy and martyred great Church of Russia and the millions of her martyrs and confessors known only to God? Judging from what these delegations declare and defend, wherever they travel outside the Soviet Union, they neither represent nor express the true spirit and attitude of the Russian Orthodox Church and its faithful Orthodox flock, for more often than not these delegations put the things of Caesar before the things of God. The scriptural commandment, however, is otherwise: “Submit yourselves rather to God than to men” (Acts 5:29).

Moreover, is it correct, is it Orthodox to have such representations of the Orthodox Churches at various pan Orthodox gatherings on Rhodes or in Geneva? The representatives of Constantinople who began this system of representation of Orthodox Churches at the councils and those who accept this principle which, according to their theory, is in accord with the “system of autocephalous and autonomous” local Churches – they have forgotten that such a principle in fact contradicts the conciliar tradition of Orthodoxy. Unfortunately this principle of representation was accepted quickly and by all the other Orthodox: sometimes silently, sometimes with voted protests, but forgetting that the Orthodox Church, in its nature and its dogmatically unchanging constitution is episcopal and centred in the bishops. For the bishop and the faithful gathered around him are the expression and manifestation of the Church as the Body of Christ, especially in the Holy Liturgy: the Church is Apostolic and Catholic only by virtue of its bishops, insofar as they are the heads of true ecclesiastical units, the dioceses. At the same time, the other, historically later and variable forms of church organisation of the Orthodox Church: the metropolias, archdioceses, patriarchates, pentarchias, autocephalies, autonomies, etc., however many there may be or shall be, cannot have and do not have a determining and decisive significance in the conciliar system of the Orthodox Church. Furthermore, they may constitute an obstacle in the correct functioning of the conciliar principle if they obstruct and reject the episcopal character and structure of the Church and of the Churches. Here, undoubtedly, is to be found the primary difference between Orthodox and papal ecclesiology.

If this is so, then how can there be represented according to the delegation principle, that is by the same number of delegates, for example, the Czech and Romanian Churches? Or to an even greater extent, the Patriarchates of Russia and Constantinople? What groups of faithful do the first bishops represent and what the second? Recently the Patriarchate of Constantinople has produced a multitude of bishops and metropolitans, almost all of them titular and fictitious. Is it possible that this is a preparatory measure to guarantee at the future “Ecumenical Council” by their multitude of titles the majority of votes for the neo-papal ambitions of the Patriarchate of Constantinople? On the other hand, the Churches apostolically zealous in missionary work, such as the American Metropolia, the Russian Church Abroad, the Japanese Church and others are not allowed a single representative!

Where in all this is the Catholic principle of Orthodoxy? What sort of ecumenical council of the Orthodox Church of Christ will this be? Already at the Geneva Conference, Ignatios, Metropolitan of Laodicea and representative of the Patriarchate of Antioch, sadly affirmed: “I sense uneasiness, for harm is being done the conciliar experience which is the foundation of the Orthodox Church.”

5. Nevertheless, Constantinople and some others cannot wait to summon the “council.” It is primarily in accordance with their wishes and insistence that the First Pre-Conciliar Conference in Geneva decided that “the council should be summoned as soon as possible,” that this council must be “of short duration,” and that it should “take for consideration a small number of topics.” And the ten chosen topics are cited. The first four topics are: the diaspora; the question of ecclesiastical autocephaly and the conditions for its proclamation; autonomy and its proclamation; the diptychs – that is, the order of precedence among the Orthodox Churches.

Evangelical objectivity obliges one to note that the conduct of the presiding chairman at the Pre-Conciliar Conference, Metropolitan Meliton, was despotic and unbefitting a council. This is clear from every page of the published acts of the conference. There it is clearly and plainly stated that, “This Holy and Great Council of the Orthodox Church which is being prepared must not be regarded as unique, excluding the further summoning of other Holy and Great Councils” (“Acts,” pp. 18, 20, 50, 55, 60).

In view of all this, an evangelically sensitive conscience cannot help but ask the burning question: what is the real end of a council summoned in such haste and in such a highhanded manner?

Most Reverend Bishops, I cannot free myself from the impression and conviction that all this points to the secret desire of certain known persons of the Patriarchate of Constantinople: that the first in honour of Orthodox Patriarchates force its ideas and procedures on all the Autocephalous Orthodox Churches, and in general upon the Orthodox world and the Orthodox diaspora, and sanction such a neo-papist intention by an “ecumenical council.” For this reason, among the ten topics selected for the council there have been inserted, indeed are the first, just those topics that reveal the intention of Constantinople to submit to herself the entire Orthodox diaspora – and that means the entire world! and to guarantee for herself the exclusive right to grant autocephaly and autonomy in general to all the Orthodox Churches in the world, both present and future, and at the same time to determine their order and rank at her own discretion (this is exactly what the question of the diptychs implies, for they concern not only the “order of liturgical commemoration” but the order of precedence at councils, etc.).

I bow in reverence before the age-old achievements of the Great Church of Constantinople, and before her present cross which is neither small nor easy, which, according to the nature of things, is the cross of the entire Church – for, as the Apostle says, “When one member suffers, the whole body suffers.” Moreover, I acknowledge the canonical rank and first place in honour of Constantinople among the local Orthodox Churches, which are equal in honour and rights. But it would not be in keeping with the Gospel if Constantinople, on account of the difficulties in which she now finds herself, were allowed to bring the whole of Orthodoxy to the brink of the abyss, as once occurred at the pseudo-council of Florence, or to canonize and dogmatize particular historical forms which, at a given moment, might transform themselves from wings into heavy chains, binding the Church and her transfiguring presence in the world. Let us be frank: the conduct of the representatives of Constantinople in the last decades has been characterized by the same unhealthy restlessness, by the same spiritually ill condition as that which brought the Church to the betrayal and disgrace of Florence in the 15th Century. (Nor was the conduct of the same Church under the Turkish yoke an example of all times. Both the Florentine and the Turkish yokes were dangerous for Orthodoxy.) With the difference that today the situation is even more ominous: formerly Constantinople was a living organism with millions of faithful – she was able to overcome without delay the crisis brought about by external courses as well as the temptation to sacrifice the faith and the Kingdom of God for the goods of this world. Today, however, she has only metropolitans without faithful, bishops who have no one to lead (i.e. without dioceses), who nonetheless wish to control the destinies of the entire Church. Today there must not, there cannot be a new Florence! Nor can the present situation be compared with the difficulties of the Turkish yoke. The same reasoning applies to the Moscow Patriarchate. Are its difficulties or the difficulties of other local Churches under godless communism to be allowed to determine the future of Orthodoxy?

The fate of the Church neither is nor can be any longer in the hands of the Byzantine emperor or any other sovereign. It is not the control of a patriarch or any of the mighty of this world, not even in that of the “Pentarchy” or of the “autocephalies” (understood in the narrow sense). By the power of God the Church has grown up into a multitude of local Churches with millions of faithful, many of whom in our days have sealed their apostolic succession and faithfulness to the Lamb with their blood. And new local Churches appear to be rising on the horizon, such as the Japanese, the African and the American, and their freedom in the Lord must not be removed by any “super-Church” of the papal type (cf. Canon 8, III Ecumenical Council), for this would signify an attack on the very essence of the Church. Without their concurrence the solution of any ecclesiastical question of ecumenical significance is inconceivable, not to mention the solutions to questions that immediately concern them, i.e. the problem of the diaspora. The age-old struggle of Orthodoxy against Roman absolutism was a struggle for just such freedom of the local Church as catholic and conciliar, complete and whole in itself. Are we today to travel the road of the first and fallen Rome, or of some “second” or “third” similar to it? Are we to believe that Constantinople, which in the persons of its holy and great hierarchs, its clergy and its people, so boldly opposed for centuries past the Roman protectionism and absolutism, is today preparing to ignore the conciliar traditions of Orthodoxy and to exchange them for the neo-papal surrogate of a “second,” “third” or other sort of Rome?

6. Most Venerable Fathers! All the Orthodox behold and realise how important, how significant today is the question of the Orthodox diaspora both for the Orthodox Church in general and for all the Orthodox Churches individually. Can this question be decided, as Constantinople or Moscow desires, without referring to, without the participation of the Orthodox faithful, pastors and theologians of the diaspora itself, which is increasing every day? The problem of the diaspora, without doubt, is a church question of exceptional importance; it is a question that has risen to the surface for the first time in history with such force and significance. For its solution there would be cause indeed to convoke a truly ecumenical council in which all the Orthodox bishops of all the Orthodox Churches would truly participate. Another question that, in our view, could and should be considered at an authentic ecumenical council of the Orthodox Church is the question of ecumenism. This, properly speaking, is an ecclesiological question concerning the Church as theandric unity and organism, a unity and organism that are placed in doubt by contemporary ecumenical syncretism. It is also related to the question of man, for whom the nihilism of contemporary, and especially atheistic, ideologies has dug a grave without hope of resurrection. Both questions can be resolved correctly and in an Orthodox manner only by proceeding from the theandric foundations of the ancient and true ecumenical councils. For the present, however, I leave these problems aside so as not to overburden this appeal with new discussions and expand it unduly.

The question of the diaspora is, then, both grievous and extremely important in contemporary Orthodoxy. However, do the conditions at present exist that would guarantee its solution in council as correct, Orthodox, and according to the teaching of the Holy Fathers? Is it possible, indeed, for there to be a free and real representation of all the Orthodox Churches at an ecumenical council without outside influence disturbing them? Are the representatives of many, especially of the Churches under militantly atheistic regimes, really able to express and defend Orthodox principles? Can a Church that denies her own martyrs be an authentic confessor of the Cross of Golgotha, or a bearer of the spirit and conciliar consciousness of the Church of Christ? Before a council takes place, let us ask ourselves whether it will be possible for the consciences of millions of new martyrs, made white by the blood of the Lamb, to speak out in it. The experience of history teaches that whenever the Church is crucified, each of her members is called upon to suffer for her Truth, and not to debate artificial problems or to look for false answers to real questions – “fishing in muddied waters” in order to satisfy personal ambitions. Shall we not remember that so long as the persecutions of the Church endured, no ecumenical councils were convened – which does not mean that the Church of God in those times did not live or function in a conciliar fashion. Quite the contrary, the age of the persecutions was its period of richest fruits. And when afterwards the First Ecumenical Council gathered, there gathered also the confessors with their wounds and scars, the bishops tried in the fire of suffering, who then could freely testify concerning Christ as God and Lord. Will their spirit be present also at this time? In other words, will the bishops of our own age who are similar to the martyrs be present at the council that is now preparing, so that this council might think in accordance with the Holy Spirit and speak and decide according to God, and that there not be heard in it primarily those who are not free from the influence of the powers of this world? Let us consider, for example, the group of bishops of the Russian Church Outside of Russia who, for all their human weakness, bear upon themselves the bonds of the Lord and of the Russian Church that has fled into the wilderness from the persecutions in no way inferior to those of Diocletian: these bishops have been excluded in advance by Moscow and Constantinople from participation in the council, and in this way condemned to silence. Let us think of those bishops of Russia and of other openly atheistic countries who will be unable to participate freely in the council or to speak and make decisions freely; some of them will not even be allowed to attend the council. Not to mention the impossibility of them or their Churches preparing in a worthy manner for so great and significant an occasion. Is this not more than sufficient proof that at the council the conscience of the martyred Church and the conscience of the ecclesiastical pleroma will both be silent, that their representatives will not be allowed even to enter – such as occurred with one of the most illustrious witnesses of the persecuted Church at the assembly in Nairobi (I refer specifically to Solzhenitsyn)?

We may leave aside the question of how moral or even normal it may be that at a time in which the Lord Jesus Christ and faith in Him are crucified in more terrible fashion than ever before, His followers should be deciding who will be first among them. At a time in which Satan is seeking not only the body but the very soul of man and the world, when mankind is threatened with self-destruction, is it moral and normal that the disciples of Christ should be occupied with the same questions (and in the same way) as the contemporary anti-Christian ideologies – ideologies that sell the Bread of Life for a mess of pottage?

Keeping all this in mind and painfully aware of the situation of the contemporary Orthodox Church and of the world in general – which has not substantially changed since my last appeal to the Holy Council of Bishops (May, 1971) my conscience once more obliges me to turn with insistence and beseeching to the Holy Council of Bishops of the martyred Serbian Church: let our Serbian Church abstain from participating in the preparations for the “ecumenical council,” indeed from participating in the council itself. For should this council, God forbid, actually come to pass, only one kind of result can be expected from it: schisms, heresies and the loss of many souls. Considering the question from the point of view of the apostolic and patristic and historical experience of the Church, such a council, instead of healing, will but open up new wounds in the body of the Church and inflict upon her new problems and new misfortunes.

I recommend myself to the holy and apostolic prayers of the Fathers of the Holy Council of Bishops of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

The unworthy Archimandrite Justin

(Spiritual father of the monastery of Chelie)

Eve of the Feast of St. George, 1977 Monastery of Chelie, Valjevo (Yugoslavia)